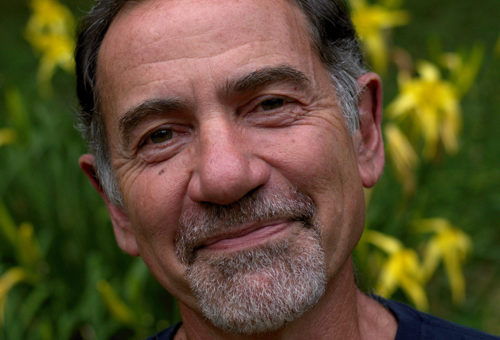

Bren Smith started fishing commercially along the northeastern coast of the United States at the age of 15. By the time he’d hit 40, he’d also fished the west coast, up into Canadian waters. But everywhere he went, it was harder and harder to make a living, as the boats and nets got bigger while fisheries declined.

Bren had had enough. Based on years of experience and a good bit of his own research, he developed a new system of shoreline fisheries management that produces oysters, scallops, mussels, and clams, integrated with two species of seaweed. This “vertical ocean farming,” as he calls it, layers the four shellfish species in columns on ropes. The seaweed helps purify the water, making for high-quality, clean seafood along with a revitalization of different fish species. It also sequesters enormous amounts of carbon, far more per acre than a forest or grassland. To top it off, some of the seaweed is harvested every year, then dried and sold as a clean, protein-rich food supplement for livestock.

Vertical Ocean Farming: an integrated system of production, where the ecological benefits and the commercial objectives are largely in harmony rather than in conflict.

This, is good for everyone. As more fishermen adopt Bren’s system, more consumers in New York and elsewhere get top-quality local seafood. Some of it reaches urban plates through community-supported fisheries (CSFs), modeled on farm-to-table community-supported agriculture (CSA). In buying their seafood from fisherman using vertical ocean farming, urban consumers also help rehabilitate the local marine ecosystem and reduce the excess carbon in the atmosphere. It’s a win-win-win.

Unfortunately, this type of approach remains the exception to the rule. In fact, the prevailing relationship between cities and the countryside in the United States is probably best described in language a social worker might use: an unhealthy mutual dependency. Rural leaders solicit tourists, markets, and capital from urban areas, often while cringing at the thought of big-city problems and decrying government interference they believe is pushed upon them by urban elites. City folk, on the other hand, depend fundamentally on the food, fiber, energy, and water that primarily come from rural places, yet regularly dismiss or disparage the inhabitants, their confounding values and backward politics. The resulting polarization and political paralysis damages people everywhere.

This dynamic must change, and quickly, not only to enable more widespread prosperity, but to reverse the decline of the ecosystems upon which all of us ultimately depend. I’m not one to label many things “URGENT,” but honestly, folks, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

The chasm between cities and rural areas, including small towns, shows up in at least three ways: politically, culturally, and economically. The political divide is much discussed of late, but that debate itself often mirrors the disconnect that created the problem in the first place. From newspaper editorials questioning whether it’s worth the trouble to enable people to stay and prosper in rural areas, to liberal pundits who almost gleefully dismiss “Trump Country,” it’s clear that many urban people have little sense of the value or even relevance of rural places. I’ve argued that rural-urban differences, while real, are exaggerated, masking many common goals and potential points of agreement on public policy.

Culturally, the distinctions that emerge between small towns and large metropolitan areas, rather than adding color to our national fabric, often become an intractable wedge that precludes real dialogue about our common interests, particularly the economic and ecological necessities that bind us together within a common fate.

The fact is that the health of rural places is essential to the health and well-being of cities. Without well-managed farms, forests, and fisheries, even quarries and mines, we won’t be able to meet our most basic needs. Without ecological management of our soils, grasslands, forests, wetlands, and waterways, the environment’s capacity to absorb and process our collective waste will continue to erode. And without thriving, lively small towns, young people migrate out, making management of our essential ecological capital highly insecure and vulnerable. Rural regions and small towns may be the first to feel the impacts, but metropolitan areas face serious consequences as well.

Bren Smith’s vertical ocean farming is one of an increasing number of examples of healthy synergies between city and country. There are plenty of others: tobacco farmers in Appalachia shifting to organic produce, which ends up on supermarket shelves in town; a New York director helping a small Georgia town reverse its economic and civic decline through community theater; community-owned wind turbines generating electricity for city dwellers, while putting income into the pockets of rural landowners, helping to revitalize small towns.

Bren Smith

Tending the farm

Overcoming the urban-rural chasm will be challenging, and won’t come quickly. But it begins by finding practical ways to create healthy synergies between cities and the countryside, and by pursuing economic and ecological policies that don’t perpetuate unhealthy mutual dependency. We’ve got plenty of real-world examples to point the way. It’s time these healthy urban-rural strategies get the attention and resources they need.

Currently running for Congress in Virginia’s 9th district, Anthony Flaccavento is a farmer and sustainable economic development consultant from Abingdon, and the author of Building a Healthy Economy from the Bottom Up: Harnessing Real-World Experience for Transformative Change (University Press of Kentucky, 2016). He writes and speaks regularly on these issues and works with communities around the world to strengthen their local economies.

To read more about Bren Smith and Vertical Ocean Farming, click here.